Henry Darger

A) At Jennie Richee not liking wind they hasten...

B) At Jennie Richee

19 x 82 inches

NL 223

Henry Darger

At Jennie Richee –

The seven Vivians, stripped are placed in fenced….

22 x 41 inches

Carbon transfer and watercolor on paper

HD 1 A,B

Henry Darger

At Jennie Richee –

The seven Vivians, stripped are placed in fenced….

22 x 41 inches

Carbon transfer and watercolor on paper

HD 1 A,B

Side a: Tells General Evans of Experiences

Side b: At Jennie Richie Violet and her sister are captured on the river with nuded girl and goods too by seven of the enemy

Carbon transfer and watercolor on paper

Side a: Tells General Evans of Experiences

Side b: At Jennie Richie Violet and her sister are captured on the river with nuded girl and goods too by seven of the enemy

Carbon transfer and watercolor on paper

NL 149 A and B / 19 x 46 inches

Side a: At Jennie Richee the Truck got trouble-some on the Plank Bridge Near a Tributary of Aronburgs Run

Side b: Left panel/ They escape again by overpowering guards.

Side b: Right panel/ Are seised by persueing Glandelinians.

Carbon transfer and watercolor on paper

NL 149 A and B / 19 x 46 inches

Side a: At Jennie Richee the Truck got trouble-some on the Plank Bridge Near a Tributary of Aronburgs Run

Side b: Left panel/ They escape again by overpowering guards.

Side b: Right panel/ Are seised by persueing Glandelinians.

Carbon transfer and watercolor on paper

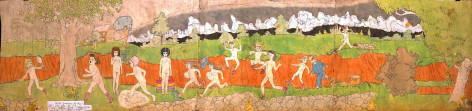

(side a) At Jennie Richee . . .Escape and pose as high class Glandelinian child scouts and work with them

Carbon transfer, watercolor on paper panels glued together

24 x 109 inches

(side b) At Jennie Richee . . .Are chased long distance by two Glandelinians with blood-hounds

Carbon transfer, watercolor on paper panels glued together.

24 x 109 inches

HD 4

(one side only) 14 x 17 inches

Golden Eagle, Poisonous Blengiglomenean Creature

Carbon transfer and watercolor on paper

REALMS OF THE UNREAL

By Stephen Prokopoff

Henry Darger was one of those people hardly anyone notices, who, seemingly, move through life as shadows. Born in 1892, possibly in Brazil or in Germany by his various accounts and perhaps bearing the surname, Dargarius, young Henry lived with his father- "a tailor and a kind and easygoing man" in Chicago until 1900. In that year the elder and crippled Darger had to be taken to live in a Catholic Mission and his son was placed in a Catholic boys' home. Darger Sr. died in 1905 and his son was institutionalized as feeble-minded, apparently on the basis of a doctor's diagnosis that "Little Henry's heart is not in the right place. " A series of escapes ended successfully in 1908. The 16-year-old Darger found menial employment in a Catholic hospital and in this fashion continued to support himself for the following 50 years. His life took on a pattern that seems to have varied little: he attended Mass daily, frequently returning for as many as five services; he collected and saved a bewildering array of trash from the streets. His dress was shabby; he was a solitary. In 1930 he settled into a second-floor room on Chicago's north side. It was in this room, more than 40 years later, after his death in 1973, that Darger's extraordinary secret life was discovered.

Amid a thick accumulation of debris- including hundreds of Pepto-Bismol bottles, nearly a thousand balls of string, old newspapers, magazines and comic books, religious kitsch and much more- his landlord, the photographer Nathan Lerner, found a creative life's work: an enormous literary and pictorial production. The key element was a picaresque tale in 12 massive volumes composed of some 19, 000 pages of legal-sized paper filled with single-spaced typing entitled The Story of the Vivian Girls, in what is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. The origins of this epic appear to be in 1909. It took more than eleven years to write it in longhand; in 1912 Darger began the task of typing the still incomplete manuscript.

The story recounts the wars between the nations on an enormous and unnamed planet, of which Earth is a moon. The conflict is provoked by the Glandelinians, who practice child enslavement. After hundreds of ferocious battles, the good Christian nation of Abbiennia forces the haughty Glandelinians to give up their barbarous ways. The heroines of Darger's history are the seven Vivian sisters, Abbiennian princesses. They are sided in their struggles by a panoply of heroes, who are sometimes the author's alter-egos. The battles are full of vivid incident: charging armies, ominous captures, storms and explosions, the appearance of demons and dragons. Darger possessed a wealth of information about military matters and particularly about the Civil War. Not surprisingly the details of battles are recorded in precise quartermaster style in supplemental volumes. In one, for example, he carefully drew and colored the hundreds of flags of the warring nations. Another lists literally thousands of names of officers in the contending armies and their fates (among these, some are described as killed while others are mortally wounded.) The true heroes of these adventures, however, are children- the favorites of God, according to the author. The epic's happy conclusion is only reached after his young protagonists survive great trials, including humiliation, enslavement and torture.

By far the most important supplement to the book, however, exists in the several hundred watercolor paintings Darger left in his room, many of them illustrations for The Realms of the Unreal. They transform Darger's apocalyptic text into a body of images that are among the most original and beautiful in outsider art. These works- pencil drawings on paper painted over with watercolor and occasional additions of collage- illustrate incidents in the book with a precision and amplitude of detail not possible in a written narrative. Textual annotations are also typically parts of these compositions, suggesting that picturing the reality of the event by every means available was a pressing need for the artist. The sizes of Darger's work range from the measurements of standard drawing pads to mural-sized works made of joined sheets of 3 or 4 feet high and as much as 10 to 12 feet long. The sheer number of large format works makes it clear that Darger conceived the epic format as appropriate to the dimensions of his vision. Because artists materials were costly, Darger's sheets usually contain finished, independent compositions on both sides. The logistics of how Darger was able to work on these large pictures in the cramped quarters he occupied are remarkable. The only conclusion possible is that he worked in the manner of scroll painters- one segment at a time. But if this is the case, memory had to be relied upon to govern the overall coherence of these exceedingly complex compositions.

There is little purpose to add to the polemic that has continued over the last several decades concerning the artistic validity of outsider art. The great emotional and formal beauties found in the best examples of this work as well as its profound influence on high art in our time would appear to have settled the matter. Darger was certainly an untutored artist in any traditional sense and his work, like that of other outsiders, stands outside of the history of art. He probably never visited a museum and had only very limited exposure to art. Yet his creative sensibility was such that it was possible for him to spin gold from the daily experience and fantasy, which in his mind easily co-mingled. If Darger was largely ignorant of art in the museums, he was in close touch with the abundant imagery of popular culture available to the pack-rat collector. Topical events are continually reflected in his texts and images just as cut-outs from newspapers and magazines, comic books and religious tracts easily found a place in his visual narratives.

Like all genuine talents, Darger developed a set of techniques that was at once individual and entirely adequate to his expressive requirements. He was at best a mediocre draftsman, for example, having particular trouble with human figures. Yet Darger created an art filled with legions of figures whose images were appropriated. Darger's method was to simply trace images from children's book illustrations, comic strips and similar sources. If the needed image was not of the required size, the artist would take it to the photography counter of a near-by drugstore and have it enlarged or reduced to the proper measurements. Frequently favorite images were repeated in a given picture as well as additional works. Other elements deemed suitable- butterfly cut-outs, Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck, fragments from coloring books and game boards and many more- were confiscated into Darger's pictures and, because of the easy alliance in them of the real and the imagined, seemed perfectly at home.

Darger's particular brilliance lies in a keen organizational sense. His major compositions bring together massive casts of characters in ways that surely would have gladdened the heart of a Cecil B. DeMille. These elaborate forces are deployed with a sure eye for intricate, often cunningly balanced relationships that activate the entire picture plane. Darger's compositions are commonly set in expansive landscapes or, somewhat less frequently, in interiors, both particularly well-suited to the horizontal format he favored.

There is a constant attention to the distribution of visual incident over both ground, sky or wall planes. Darger's skies, for example, are always active, often with storm clouds and networks of lightning or with cloud forms containing double images of figures or faces. As a child, Darger witnessed a devastating tornado, and skies with rolling clouds and electrical fireworks are often present in his more turbulent scenes. I benign settings the artist contrives rich and colorful patterns in depictions of crowds of children, flowers and radiantly colored insects.

One of the most appealing and consistently rewarding aspects of Darger's art is his sumptuous feeling for color. His richly orchestrated palette reinforces compositional structure and provides treasures of felicitous and often unexpected harmonies. Even in the most pale and subtle combinations of hue, Darger establishes chromatic relationships that are opulently atmospheric.

Darger's imagery, when it details mayhem and sometimes the lurid mistreatment of little girls, can be distressing. An observer characterized a picture in a sunny landscape in which images of children, exotic flowers, butterflies and exploding bombs were joined as being like Beirut. The only possible response in such instances is that art, being often fashioned from artists obsessions, is rarely a vehicle for the description of perfection: Darger created art from the visions available to him.

Viewers are also perplexed by the clearly androgynous anatomy of Darger's nymphets, curiously enough a trait never in evidence among the seven angelic Vivian girls. It is not possible to fathom the causes or intricacies of Darger's fantasies, but it should be said that his public behavior appears to have been without blemish. A saintly man who frequently attended Mass, Darger saw himself as the ardent protector of children. He could, therefore, in his words and images, subject his creatures to terrible trials from which it was in his power to rescue them. The wars, fires and tempests that form the context of his art undoubtedly reflect an unconscious conflict that seems to have given him little respite. God was Darger's protagonist and consequently the conflict could be nothing less than cosmic. This poignant struggle is extensively documented in the artist's diaries, which record by turns his pleading and rancorous exchanges with the Creator. If Darger's fantasies often hovered on the fringes of sanity, his art enabled him to transform his obsessions into a luminous production that, in its best moments, transcends the pain and circumstances of its making.

-from A Personal Recollection by Nathan Lerner

An Approximate Chronology Of The Life Of Henry J. Darger, As Reconstructed From His Own Diaries And Journals

April 12, 1892

Henry J. Darger born. Lives with father- "a tailor and a kind and easygoing man"- in a "small, two-story house on the south side of a short alley between Adams and Monroe, " Chicago.

1900

Father crippled and goes to live in a Catholic Mission, Little Sisters of the Poor, Chicago.

1905

Taken to asylum and works summers on nearby farms. Father dies.

1908

Runs away from asylum.

1913

Witnesses the Easter Sunday twister at Countrybrown, Illinois, in which entire town is destroyed.

1916

Begins typewriting Realms of the Unreal on April 30.

1917

Drafted.

1918

Dismissed from the Army for eye trouble. Returns to employment at St. Joseph's Hospital. Among other duties, washes Sisters' latrines.

1922

Employed Grant Hospital, Chicago.

1930

Moves to room on Chicago's north side.

1945

Registers for conscription.

1947

Employed at Alexian Brothers Hospital, Chicago. Washes dishes, rolls bandages.

1963

Forced to retire due to illness, November 19th. After that, he "barely makes it" on Social Security.

1966

Begins to write My Life History. Rarely crosses out a word.

1972

Taken to the Little Sisters of the Poor, Chicago, after lameness and other sickness. Dies 6 months later.